Finding IP Value

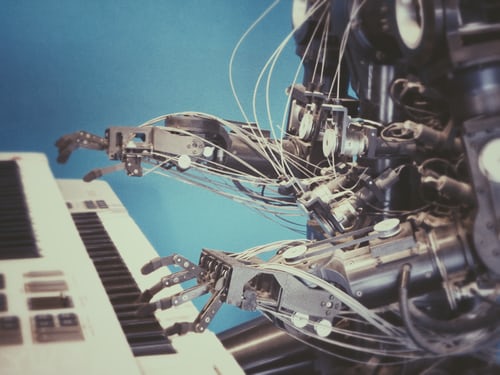

Domo Arigato, Mr. Roboto: Can Artificial Intelligence be Listed as an Inventor on a Patent?

By: Matt Lubozynski

Recently, the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia decided whether the Patent Act requires that an inventor be a human being versus artificial intelligence in order to be granted a patent. See Thaler v. Hirshfeld, No. 1:20-cv-903 (LMB/TCB), 2021 EL 3934802 (E.D. Va. Sept. 2, 2021). Under the Patent Act, Judge Brinkema decided that artificial intelligence cannot be an inventor.

In reaching this decision, Judge Brinkema first deferred to the United States Patent and Trademark Office’s (USPTO) earlier determination that an inventor had to be a human being based on its interpretation of relevant provisions of the Patent Act. Id. at *4. However, the Court went further and stated that even without the deference afforded the USPTO, its decision was correct under the law. Id. This was due to the fact under the Patent Act, which was most recently amended in 2011, there is an explicit statutory definition for the term “inventor,” which means “the individual, or if a joint invention, the individuals collectively who invented or discovered the subject matter of the invention.” Id. at *5 (quoting 35 U.S.C. § 100(f)) (emphasis added). As the Court found, “’individual’ ordinarily means ‘a human being, a person.’” Id. at *6 (internal brackets omitted). There were also other instances throughout the Patent Act, as well as the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the term “individual” under a different statute, that made clear that artificial intelligence could not classify as an inventor as it required a human being. See id. at *5-6.

The Court did not solely rely on the words within the Patent Act in making its decision. The Federal Circuit, which has exclusive jurisdiction over appeals concerning patent matters, see 28 U.S.C. § 1295(a)(1), previously held under current patent law that “inventors must be natural persons.” Id. at *6 (citations omitted). Although the decisions relied on did not involve artificial intelligence, but instead corporations being named as inventors, the Court found that the unequivocal statements by the Federal Circuit that inventors had to be natural persons “support the plain meaning of ‘individual’ in the Patent Act as referring only to a natural persons and not to an artificial intelligence machine.” Id.

With neither facts nor law on his side, Plaintiff resorted to the stand-by argument of policy. Id. at *7. Plaintiff attempted to argue that patents should be allowed for artificial intelligence generated inventions as it would lead to more innovation and failing to allow it “threatens to undermine the patent system by failing to encourage the production of socially valuable inventions.” Id. Plaintiff also argued that there was a moral component to allowing artificial intelligence to be listed as an inventor as, if it is not permitted, “allowing people to take credit for work they have not done would devalue human inventorship.” Id. The Court did not buy these arguments, especially in light of the Patent Act’s clear, unambiguous language concerning who qualifies as an inventor and the “overwhelming evidence that Congress intended to limit the definition of ‘inventor’ to natural persons.” Id. at 7, 8. The Court further quoted from an USPTO report regarding artificial intelligence and patent policy which found that artificial intelligence is not quite to the point where it could invent or author without human intervention. Id. at *8. Because of this, the USPTO felt that a modification in intellectual property law was not required, at least as of the August and October 2019 timeframe when the USPTO issued the report.

In the end, Judge Brinkema acknowledged that “[a]s technology evolves, there may come a time when artificial intelligence reaches a level of sophistication such that it might satisfy accepted meanings of inventorship. But that time has not yet arrived, and, if it does, it will be up to Congress to decide how, if at all, it wants to expand the scope of patent law.” Id. at *8. Such a time may not be far off as South Africa appears to have recently granted a patent to an artificial intelligence system. See Meshandren Naidoo, In a World First, South Africa Grants a Patent to an Artificial Intelligence System, Quartz Africa (Aug. 9, 2021), available at https://qz.com/africa/2044477/south-africa-grants-patent-to-an-ai-system-known-as-dabus/. However, at least for now in the United States, robots receiving patents as inventors will have to wait.